Why learn craft in the age of automation?

The costs of masterpieces on demand

I spent the pandemic lockdown trying to get good at something I was intrinsically horrible at: painting. It was a way to escape the soul-sucking screens of my laptop, phone, and Netflix.

From YouTube videos and a six-month Skillshare trial (remember that pandemic perk?), I learned how to paint with gouache, my medium of choice. Gouache’s opacity made it much more forgiving for beginners than watercolours, which are transparent and will magnify any wrong brushstrokes. My first Skillshare instructor guided me to create leafy shapes by using a round brush dipped in sky blue paint. I created my first page of scumbly flowers, a painting that will forever live in a sketchbook, but it kickstarted over 500 hours of practice and a self-published art book.

Just when I thought my sketches were presentable, technology reached a conspicuous milestone. Generative AI became available to the masses in October 2022, a direct smack to my craft. Midjourney and DALL·E captured the visual art of photography and painting. Anyone could prompt their way to their ideal image.

My initial reaction was surprise, then defeat. Was this one machinery (spread over many servers, but still) going to take over the skill I worked so hard to learn? I created some AI images and compared them to my sketches. The Midjourney paintings were crisp, vibrant, and looked like a fully developed image. It’ll take me a few years to be able to render an image that way.

Something felt off with the AI-generated images. The anodyne images look very artificial and have a digital smell to it, the kind with perfect gradients and vibrant colours. But this is AI still in its infancy. What happens when AI gets so good that we can’t ignore it?

Will AI harm me as a creative? Will it deprive me of the activity I enjoy doing and snatch my chance to make my mark onto this world? Why waste time learning how to do things well when machines can do it for us?

I understand why people have flocked to AI. It’s enticing to know that it could be a shortcut for humans to get instant, seemingly professional work on demand. We don’t need to learn how to draw, we can just ask DALL·E to whip up a surrealist political cartoon for us. We don’t need to make PowerPoints and figure out the best storyline to deliver our ideas, Canva will do it. We don’t need to write anymore, Notion will draft a business memo and Grammarly will edit it. We’re seeing the shiny new toy syndrome hit the internet on a mass level.

Despite this magic button, easy involves risk. When we automate art, we lose the process of art: the resilience it takes to learn and fail, the companions made along the way, the transferable skills, the resulting work that anyone could be proud of. The slower, more arduous process of learning a craft is worth more than any shortcut.

500 hours of painting

As the internet picked up on Midjourney and DALL·E, I continued to learn how to paint. These are my learnings through 500 slow hours of filling out seventeen sketchbooks:

Riding the learning curve

Learning art taught me of the psychological power of learning curves. Typically, I look for the easy route. But when something is hard, and I suck, but I take action to not suck, that can lead to a whole identity shift and eventually, a confidence shift.

After I laid out my student-grade paint, I pressed “skip” on the first Skillshare lesson about “colour charts”. I was certain that yellow and blue made green. Yet when I mixed the yellow and blue paints, I got a very dark green. I added white, hoping it would brighten up the mix but, instead I just ended up with a puddle of faded, sage green. Where was I going wrong? This is impossible. I went back to the foundation lesson and unlearned what I thought I knew.

Then came my next struggle: drawing people. This is probably why stick figures rule. I know that a person is made out of limbs and joints but the figures I insert into my sketches would look out of place because of 1) scale (there’s a tendency to make heads too big because our brain puts extra emphasis on people’s faces), 2) have awkward poses (joints only move limbs in certain directions), or 3) seem floating in the air (this is a problem where the feet don’t exactly touch the ground).

Mistakes helped me learn. I learned that some colours tint stronger than others, so a drop of my prussian blue would overpower the mix when a drop of cerulean blue won’t. I learned that people’s heads are always at eye level, so I should line up the tops of people’s figures for them to fit the scene.

Looking at my first few sketchbooks made me see how far I’ve come. I’ve improved quite exponentially over the last few years and that’s largely because of the hours and the conscious effort I put in. Every expert must have started somewhere. I bet Leonardo da Vinci sucked at drawing a woman looking straight ahead when he first started (don’t fact check me on that). I was not an exception.

I don’t know if generating art through AI presents the same learning curve. Prompt engineering could be a skill that evolves with time and the development of AI, as is with other technical skills like coding HTML5 or Javascript. I could input a few different keywords and get a completely different image. Getting decent at keyword prompting could maybe take 5 hours, a cheaply acquired skill. Or I could put in 5,000 hours and actually learn how to paint.

The slow process of learning continued to challenge me, but I was now committed, convinced that my efforts will yield results. I found pockets of time in between my full-time job to practice, read on art theory, and watch more demonstrations on YouTube. If I was willing to learn and put in scores of hours in front of a blank page, I could get better.

I applied this belief to other parts of my life too. I wasn’t a runner, but I have done several 5K races. I didn’t know how to shoot good photos with film, but my friend taught me how to expose frames correctly and I practiced. Now that I know I’m capable of learning new things, I can go the distance.

Real-life dopamine hits

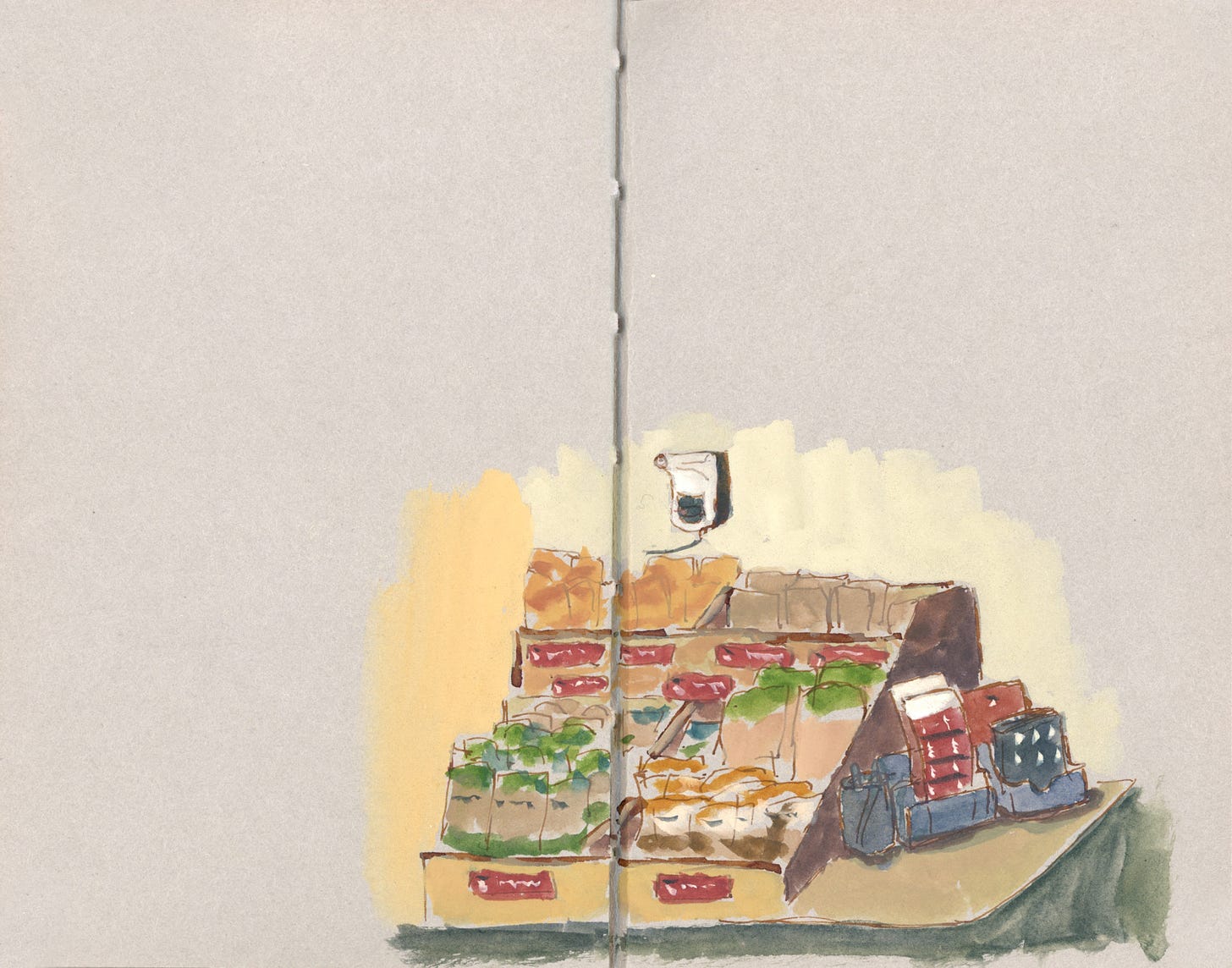

As I got better with painting at my desk, I wanted to take my skills outside to paint real landscapes and real people. The French call this painting “en plein air”. I began hunting for new areas of Hong Kong I haven’t visited. I checked the local observatory for live pictures of different locations to see which areas have glorious clouds to paint. When I happen to arrive at a lunch appointment early, I would giddily whip out my sketchbook because it meant I had fifteen minutes to paint the side profile of the stranger sitting across from me.

Painting is now my favorite activity to do outdoors. It’s a good excuse to stay by the waterfront and breathe in the salty air for half an hour while I fill in my sketchbook with sky blue hues. I sometimes have a glass of ice cold bubble tea with me, too. After a while, I mustered up the courage to bring my paints out when my friends were hanging out at a bar. The relaxed environment lends itself well to some sketching on the corner of the table.

I’ve made friends too on this journey. I had bought a homemade easel shipped from Vancouver and made a YouTube video about it. A painter from Hong Kong reached out with some questions. We now do most of our plein air sessions together.

When I traveled to Melbourne this year, I saw a familiar-looking guy with the same easel that I have. I approached him and his friend, not realizing that I follow them both on Instagram. I got an invite to paint with them for an hour at Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens the next day.

A finished painting, whether good or bad, would give me a sense of accomplishment. I did that. I really put in one hour of work and painted that scene. I’ve tried to mimic this painting through generative AI tools but didn’t get the same dopamine hit. Cycling through the four variants that Midjourney creates felt more like a lone task than an enjoyable activity where I could meet friends. AI turned painting, photography, and visual art into a commodity that costs $8 a month.

A new artistic lens

Having learned how to paint, I now see the world through an artistic lens. I cherish the blue hour and the cool light that illuminates the trees, to appreciate the restaurant staff chatter as I try to project a visual of my food onto my sketchbook, to be swept away by a romantic audiobook as I sit by the docks and paint the boats. I have seen many sunrise landscapes in solitude, mainly because my friends abhor that I get up before dawn at all. My gosh when the golden rays hit the grounds — magic.

I used to shrug at art exhibitions because we have photography now, what’s the point of painting? After I took painting seriously, I can see how artists make choices on composition, colour temperature, values. I can admire and stare at them in my local museum. I look through Dinotopia creator James Gurney’s sketchbooks and they are so dense with storytelling and life.

Over time, I realized the learnings I got from painting bled into my other crafts. My primary skill is in writing, having done it professionally for the past six years as a journalist and copywriter. I also take photography seriously and have even covered events.

The composition theories in photography like the rule of thirds apply to paintings. An off-center but strategically placed subject creates a dynamic and interesting image. I wouldn’t know what a good visual work of art is if I didn’t burn the rule of thirds into my subconscious.

I’ve also learned that there should only be one main idea in each piece of writing. My art teacher Jared Cullum once said in class that he would cut his painting in half if he saw that there are two subjects in one painting. Both examples are applications of the same concept.

Every writer makes a conscious choice of the order of presenting information to readers, starting with the hook they want to lead you in with at the top, the body in the middle, and parting thoughts at the end. I have yet to learn how to apply this into visual art, but I think framing is one way to do that.

Learning about these three crafts continuously trains my eye. I become sharper in all three with each advancement in one.

Click-to-generate images shortcuts the process. What is the composition? What is the colour palette? Should the painting be high or low contrast? AI makes these choices for us, whereas if we’re creating this image from the ground up, we would have to decide at every step.

I’ve come to appreciate artists’ decisions and notice craft out in the wild: light, colour, composition. These all feed back into inspiration for my next piece of art. It’s a virtuous cycle of continuous creation.

Masterpieces on demand

The path of an artist's development doesn't stop just because technology provides shortcuts. Illustrators still find work even as photography became commonplace. Muralists still zhush up walls even though wallpapering is an option. Handmade pottery is still around even though machinable ceramics are more cost-effective.

I love technology. I use it all the time. For all my professions of love for the analog notebook and fountain pen, my primary notepad of choice is the Roam and Notion apps on my phone. My smart watch never leaves my wrist because I want it to track every calorie and heartbeat. I even use AI features in Photoshop and Lightroom to enhance images.

Where I draw the line is having it replace the act of creating. I still don’t imagine a situation where I would copy onto paper an image generated by Midjourney. The action of painting is an activity that sparks excitement, joy, and fulfillment out of me. I don’t want to outsource those feelings to some silicon chips.

Even with the knowledge that it can currently paint better images than me, I still choose to hone in on the craft of painting. I choose to be more disciplined, applying rigor into my practice, completing my homework, painting outside when I can in order to level up. I choose to be proud of the work I can make, not of the keywords I input into a prompt machine.

Every painting goes through an “ugly phase”, where the canvas is splattered with disparate blobs. The only way to get a good result out of a painting is to work through the “ugly phase”, create bold strokes around the blobs and accent it with details that bring a painting to life.

In a similar way, I’m so glad I stuck through the “ugly phase” of my painting learning journey to see myself become a different person on the other side. I unlocked the confidence to pick up a new skill from scratch, even as I learned it in my adult years. I learned how to enjoy an activity as a hobby, something I struggled to do because I was fixated on “being productive”. I figured out some transferable knowledge: how some of my painting knowledge could be implemented in my writing and how my photography composition skills apply to painting. I was able to view the world in a new light, one where everything becomes a subject to paint and one where I could appreciate the world as art.

I can’t keyword-prompt any of those feelings to life.

This mass embrace towards AI at its best is human laziness and at its worst is a destruction to human craft. I worry that people will be lazy and just entrust their self expression, their essence, their future potential, to AI. I worry that when it boils down to it, the extent of being a good craftsperson is being good at generating prompts, that people’s love for a craft will also be fatally wounded en route to AI race. I worry that people become accustomed to instant, machine-generated, good-enough work and the next generation would never be in an environment that nudges them towards genuine creativity.

I can imagine the skeptics that rendered painting obsolete when colour photography became common. Yet painting still exists, so I have hope that the pursuit of crafts have the ability to endure through technology.

I hope that the future generations still turn back to the analog, similar to how people of my generation try out film photography and typewriters. That out of curiosity, they may stumble into a slow, old process of creating in an unfamiliar lane with results that may take years to hone in. And maybe, just maybe, they fall in love with a new craft.

Thanks for kickstarting this essay with his curiosity. And big big big thank you to who guided me to my first long-ish essay from sketch to the finished result.

Update log:

📖 Read two great essays by Ursula Le Guin: Death of the Book and Staying Awake. Both were recommendations by

because they relate to this essay in a way.📹 I’m back on YouTube! Kind of. Ahead of some travels, I did a video on my updated 2024 travel kit for gouache (which honestly hasn’t changed much).

🌄 The rain cleared up for one day of sunshine, and I grabbed that chance to go take pictures of the sunset. I’m experimenting with overexposing shots to achieve pastel tones. A challenge with such high dynamic range images.

🎮 Playing Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney - Dual Destinies. I love that they introduce new features in each game with a storyline, and not just a gimmick. I’m on case #2.

📖 Reading The Millionaire Fastlane by MJ DeMarco (74% completed). I’m finally getting to the meat of the book. Or at least, I found the insights I was searching for.

🩺 Did a body composition scan at my gym. Results all point to “optimal” or “under”. It’s satisfying to know that cardio is boding well for my body.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning that I may receive a commission if you make a purchase through the links at no cost to you.

I want to thank you and every other artist in the world for taking the time to make beauty with your hands.

One artist to another, I wanna say—good job!